Manatees seek out this strange spot in the winter

Over the past several years, we have spent a lot of time in Florida. Before we RVed, we took trips to the Everglades, Tampa, and Disney World. We have visited Anthony's parents at their Florida house. We took our East Coast Road Trip in 2017, which brought us to Jacksonville, Daytona, Miami, and the Florida Keys. Then in our RV life, we have traveled to Florida all three years. So it might come as a surprise to learn that we had never seen a manatee.

The main reason for this is that we were always in the right place at the wrong time. Manatees spend most of the year in the ocean, but they come inland in the winter to seek warmer water. Our Florida trips were almost always in spring, and by that point the manatees were already venturing back out to sea. Our winter trips to Florida only included a couple of days in the Everglades, and a couple of days last year along the Panhandle.

This year was different. We made our way down to Florida by mid-January, which is prime season for manatee viewing, and we'd be spending at least a month in the state. We had been patiently waiting for the right time to finally check off our manatee sighting on our RV Wildlife Bingo card, and there would be no better time than now.

Florida boasts many locations for manatee viewing, and in some locations, you can even swim with the manatees! From a safe distance, of course, as these beautiful creatures used to be endangered and are now threatened, meaning they're still at risk and they/their habitats must be treated delicately. We found ourselves camping near couple of viewing locations and couldn't wait to spot our first "sea cow."

The funny thing was, though, we were so looking forward to seeing them, but we knew practically nothing about them! We knew they used to be endangered, they are mammals, and they are gentle giants. More research was definitely needed. Suddenly, our quest to see them also became our quest to learn as much as possible about these odd blobs of the aquatic world.

The manatees that we find in Florida are one of three species, the West Indian Manatee. The other species are the Amazonian Manatee and the West African Manatee. Strangely, those other species live exactly where you'd expect given their name. Has there ever been a petition to change the name of the West Indian Manatee to the Florida Manatee, just to avoid confusion? This is precisely why you often hear people call them that.

Our first stop was at the Manatee Viewing Center in Apollo Beach, FL. The accolades speak for themselves, with this center being voted in the top 10 best free attractions in the country by USA Today. The Viewing Center has walkways that offer observation points overlooking a channel where the manatees come to get warm. In addition, there is a cownose ray exhibit, an education center, cafe and gift shop, kayak rentals, walking trails, an observation tower, and access to the Sea Turtle Rehabilitation Center run by the Florida Aquarium. School groups have ample space for picnic lunches, shuttles take you anywhere you want to go, and did you catch what we said earlier? It's all FREE!

Sounds idyllic, right? Well, there's a catch. The Viewing Center looks like this:

It also smells how it looks.

This is the discharge canal of the Big Bend Power Plant, run by Tampa Electric. Although most Instagram-worthy shots are of manatees in the warm-water springs of Central Florida, only about 15% of Florida manatees go there in the winter. 60% make their way to electric plants, and the remaining 25% find basins that are warm enough to survive, but these pose a risk because they are less predictable. This year, many of the springs and power plants had record numbers of manatees, which is good because they survive better in these habitats.

Back in the day, human interference impacted the manatees' ability to access most of the warm springs where they used to go in winter. Navigation locks, flood gates, and fishing nets contributed to this interference. So, they started hanging out near power plants instead, because of the warm water in the plants' discharge canals. In the 1970s, the power companies were starting to get pressure nationwide to build cooling towers instead of discharging water, to protect coastal marine ecosystems, but because the manatees were endangered and dependent on the heat, the power companies in Florida were able to keep discharging some hot water to protect them, saving billions in the process. Ironically, some plants are now actually required to keep the hot water flowing, with even temporary shut-downs being strictly prohibited.

So, even though this may not be the most picturesque setting for observing the manatees, it really is a wonderful depiction of human efforts to decrease threats to wildlife.

We weren't sure just how many manatees would be in the waters when we visited. Would they be tough to spot? The answer to that is no. As soon as we arrived to the observation walkways, we looked down to see hundreds of openings in the water, where the manatees were just barely scratching the water's surface. Then, bubbles and ripples would form, and there one was, coming up for air.

You simply cannot watch manatees without them bringing a smile to your face. They just look so cute and playful! They spent most of their time bobbing up and down, rolling, and even breaching like little round dolphins! However, they're not actually related to dolphins. Their closest living ancestor is the elephant.

We had so many more questions, and so we ventured into the education center. Here, we learned that Anthony is not tall.

And if you've been feeling better about yourself after seeing these animals because you're still carrying some holiday weight, sorry to disappoint you, but manatees are not actually fat. Their big size is mainly due to bone structure, skin, and intestines. The reason they need to seek out warmer water in the wintertime is because they cannot survive in waters colder than 60°F. Even when they flock to the ocean in summer, they stay near the coasts because the depths of the ocean would be too cold.

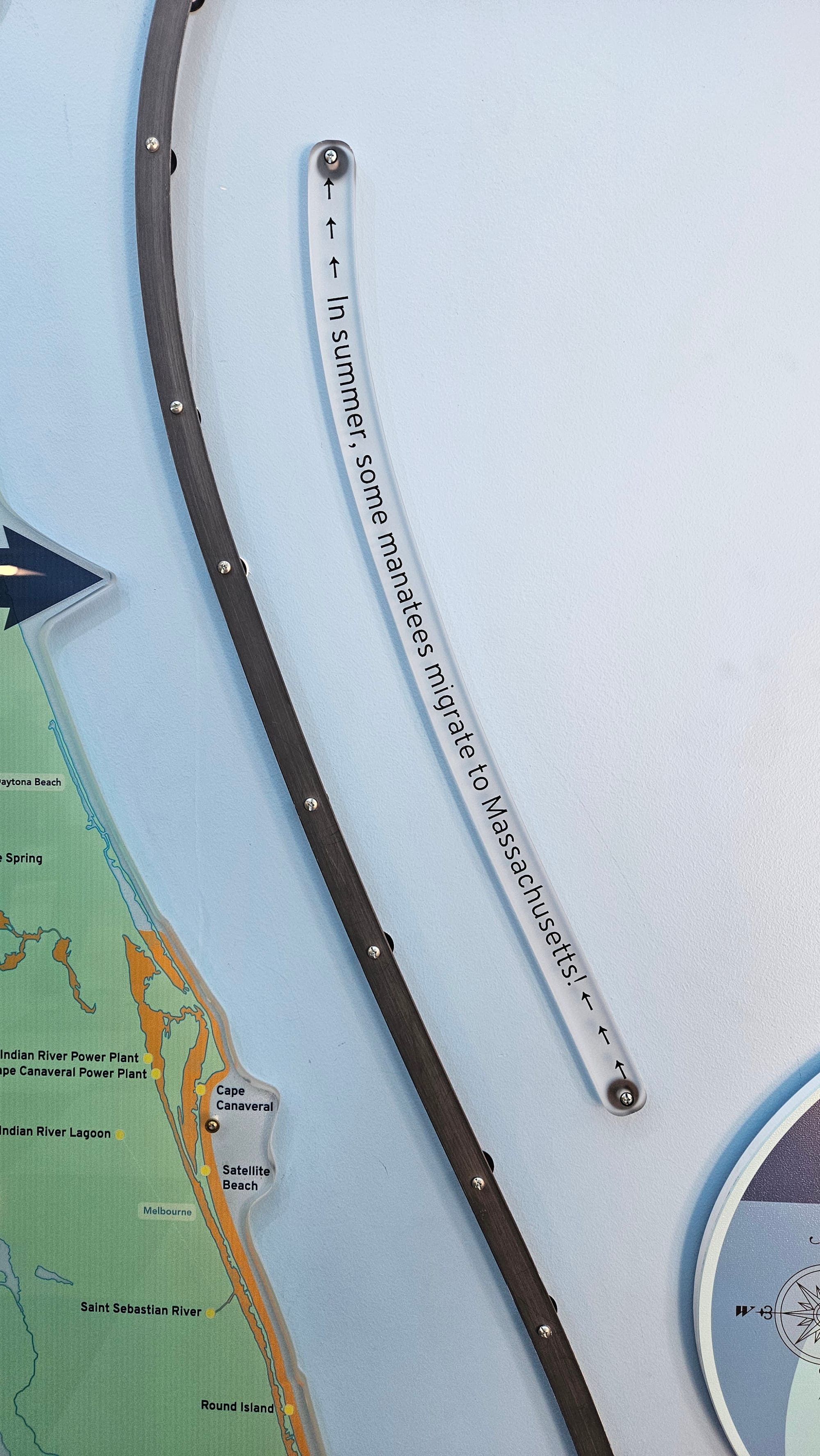

This is also why they typically stay south, along the coasts of Florida and Georgia, but to our surprise, some have been known to venture quite a bit northward, migrating all the way to Massachusetts! Man, if we still lived up there, we can only imagine the day we're sitting on the beach and spot a manatee. We would have been very confused.

As much as we want to just focus on the loveable cuddliness of these floating potatoes, we cannot ignore the much darker side to the manatee's history and what contributed to their endangered, and now threatened, status. In short, they are vulnerable creatures. There were only a few hundred left in the 1970s, because of poaching, habitat destruction, and boat collisions. Then, the success of conservation efforts over the next several decades increased the population to about 13,000 as of 2016. They continued to suffer through dangers to their population, though, with a quarter of recorded deaths in the 1980s-2000s caused by boat collisions, and red tide in 2021.

Keeping the manatees alive helps humanity in surprising ways. Because they are herbivores, they eat sea grass, and some sugar plantations and water treatment plants rely on them to keep discharge and irrigation canals weed-free.

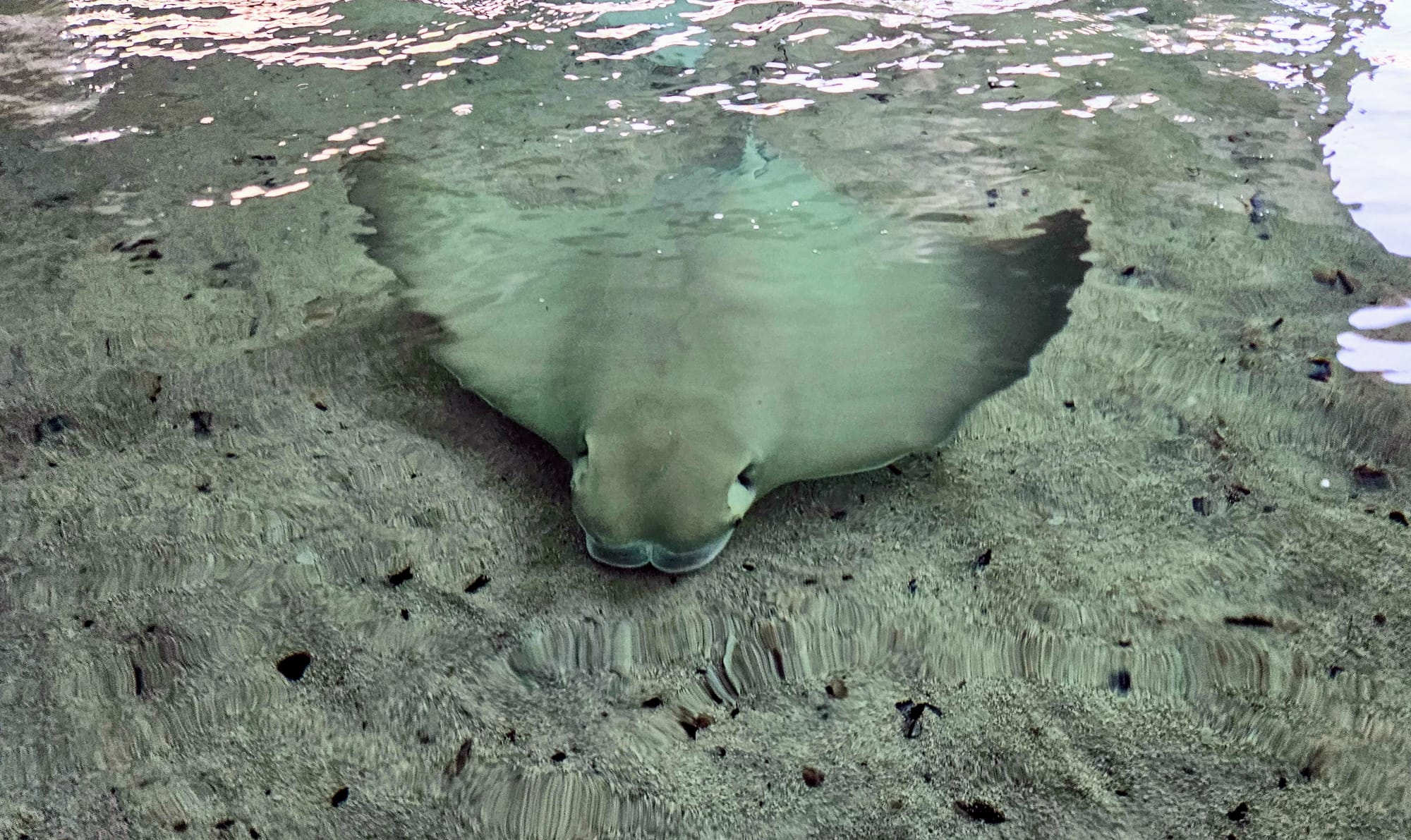

We acquired all the knowledge we could fit into our brains for one day, and so it was time to head downstairs to see the rays. We were allowed to put our hands in the water as the rays swam by, with instructions to try to gently touch their fins with two fingers. Cownose rays can sting when threatened, so it's best to not approach them aggressively or touch their heads.

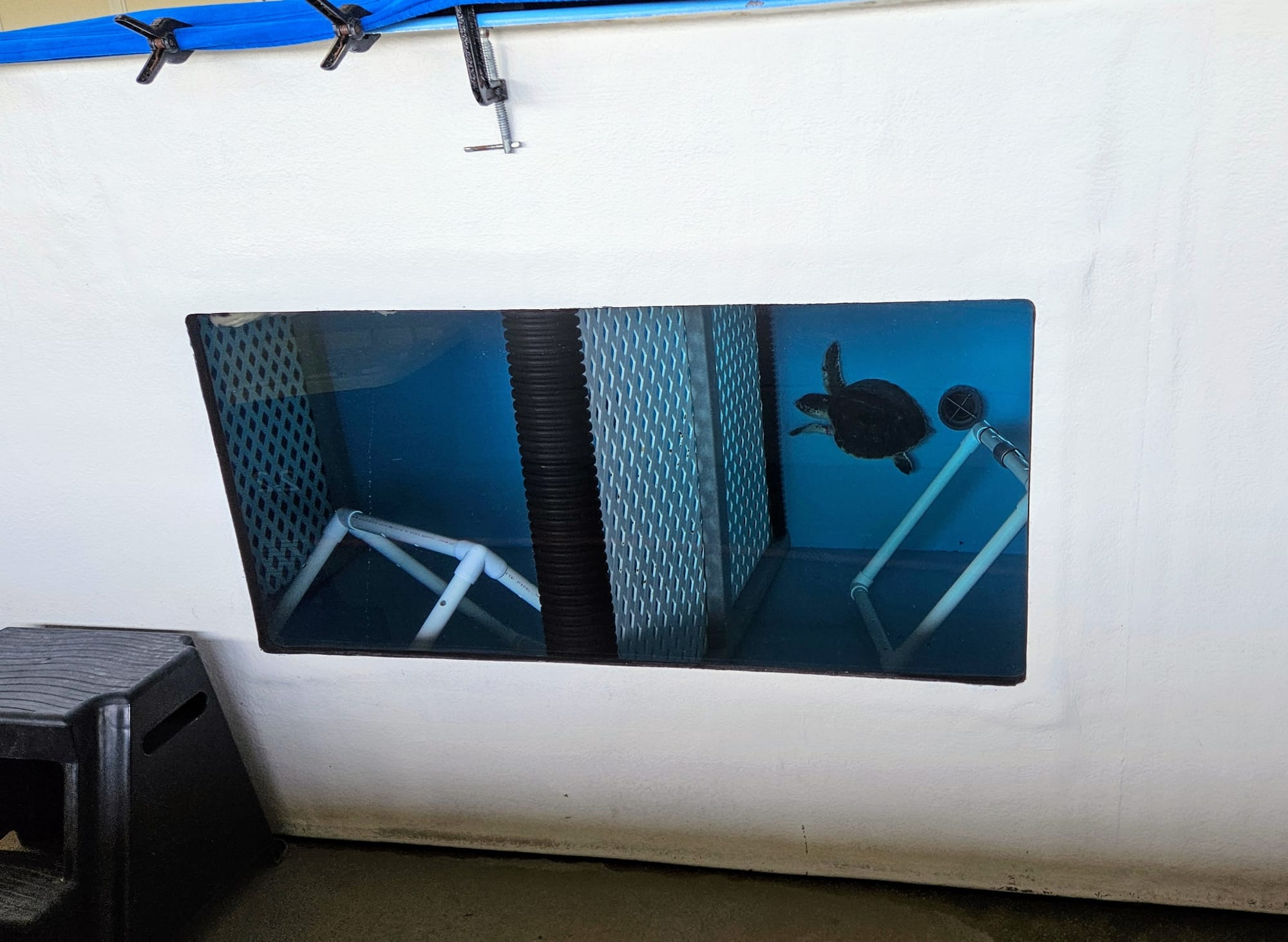

We then took a walk on the nature trail, stopping at the observation tower and then heading to the Sea Turtle Rehabilitation Center.

A couple weeks later, we switched campsites and moved south to North Fort Myers. We were only 10 minutes away from Manatee Park, a place we wanted to go two years ago when we were staying in the area, but we were too late in the season to see manatees. This time, we hoped we would have more luck.

Manatee Park's warm-water refuge is also discharge canal, for the Fort Myers Power Plant, but the power plant is a tad less prominent, making the park feel a little more natural and landscaped. There is a walk alongside the canal for manatee viewing, plus kayak rentals that, from our standpoint, looked like they'd get you closer to the manatees than the rentals at the Viewing Center, which were mostly just through the nearby waterways. We expected more information on the manatees, but besides a couple of pamphlets and a video that was running on loop, we didn't see much, which would have been disappointing had we not already soaked in manatee trivia a couple weeks prior.

On this day, the canal water was actually slightly cooler than the gulf, so the manatee count was low. We also went at a time of day where the sun was reflecting off the water, making visibility poor. Still, we remained patient as we observed the waters, and soon we spotted the little ripples in the water, the unmistakable sign of the manatee. Most seemed to be moving towards the river, not surprisingly because that water was warmer too, but we got to see about a dozen of them making their way down the canal. When manatees are active, they can hold their breath for an average of 3-5 minutes. When they're resting, they can last under water for up to 20 minutes! These manatees were actively moving, and so we saw a lot of little head bobs and breaches above the water's surface.

Between the low numbers, the sunlight, and the less clear water, we definitely had fewer opportunities to get good photos of the manatees here, but the park itself was nice to explore. It's a small park, and we finished walking all the pathways in about 20 minutes at a leisurely pace. One walkway leads into the mangroves, with lookouts to the river, which was pretty.

Though we couldn't easily get our answers at Manatee Park, we still had some lingering questions after our two excursions. Obviously, they live in large groups when they seek warm refuges in the winter, but is this always the case? Turns out it's not; in the warmer seasons they are solitary creatures, unless they are young or mating. Calves remain with their mothers until 2 years of age. As for the mating ritual, the males sense when the female is in estrus, and they form a herd and follow her around to mate with her. The more you know!

And with that invaluable knowledge, we closed the door on our manatee adventures...for now. Next time we find ourselves in Florida in the winter, we will likely prioritize swimming with them, because that would fill us with the utmost glee. But until then, let's continue keeping these babies alive and thriving!

To sponsor a manatee or donate to conservation efforts, click here.